Malaria continues to be a global health crisis, claiming over 600,000 lives annually, with African children under five being the most affected. However, a groundbreaking study published in Nature by an international team of researchers offers hope for new treatments and vaccines targeting severe malaria.

The research, conducted by scientists from EMBL Barcelona, the University of Texas, the University of Copenhagen, and The Scripps Research Institute, has identified human antibodies capable of recognizing and neutralizing key proteins associated with severe malaria. These findings could revolutionize the fight against the disease.

Severe malaria is caused by the parasite Plasmodium falciparum, which infects and alters red blood cells. This modification causes the cells to stick to the walls of small blood vessels, particularly in the brain, leading to impaired blood flow, brain swelling, and, in extreme cases, cerebral malaria.

A family of proteins called PfEMP1 on the surface of infected red blood cells plays a critical role in this process. Some PfEMP1 proteins bind to EPCR, a protein on blood vessel linings, causing damage that leads to life-threatening complications. Despite its importance, PfEMP1 has been a challenging vaccine target due to its high variability.

Researchers, however, discovered two human antibodies that can broadly target PfEMP1 proteins. These antibodies specifically recognize a conserved region known as CIDRα1, which binds to EPCR. Using advanced immunological screening methods developed at the University of Texas, the team identified these antibodies as potential tools to block severe malaria.

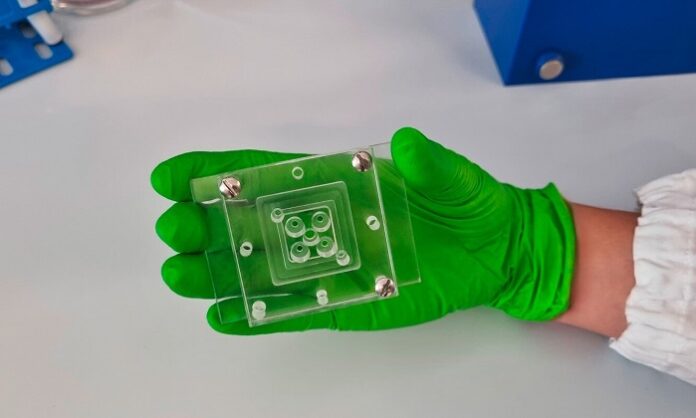

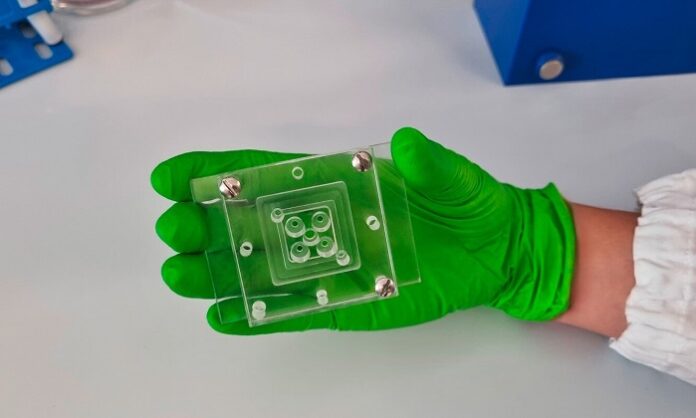

To test their efficacy, researchers developed a lab-grown network of human blood vessels and simulated malaria infection. This innovative “organ-on-a-chip” technology demonstrated that the antibodies effectively prevented infected red blood cells from sticking to the blood vessel walls, a critical step in severe malaria progression.

“Our experiments showed striking results,” said Dr. Viola Introini, a postdoctoral fellow at EMBL Barcelona and co-first author of the study. “The antibodies visibly stopped infected cells from adhering to the vessels.”

As reported by medicalxpress, further analysis by collaborators at the University of Copenhagen and The Scripps Research Institute revealed that these antibodies function by targeting three conserved amino acids on CIDRα1, offering insights into acquired immunity against severe malaria.

“This discovery lays the foundation for developing vaccines or treatments targeting severe malaria,” said Dr. Maria Bernabeu, co-senior author and Group Leader at EMBL Barcelona. “Our interdisciplinary collaboration and tissue engineering innovations are pivotal to studying complex diseases like malaria.”

The findings highlight the potential of antibody-based interventions to protect against severe malaria and underscore the importance of global scientific collaboration in tackling pressing health challenges.