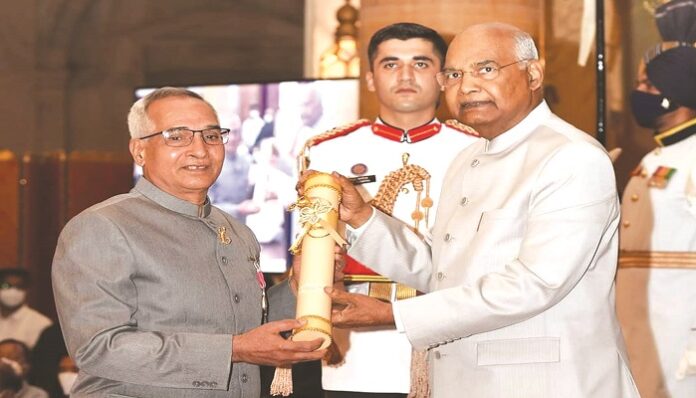

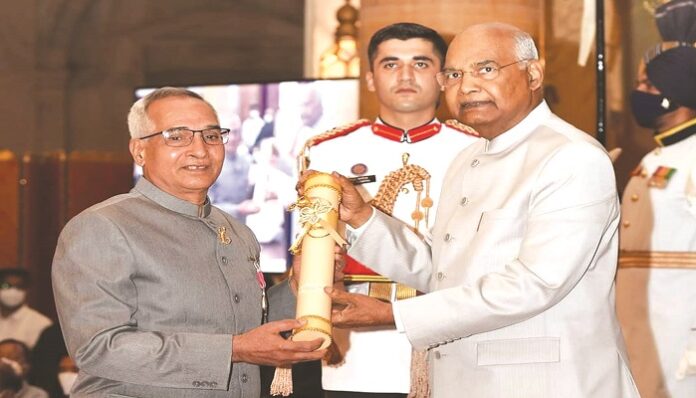

For over four decades, Padma Shri awardee, Dr Himmatrao Saluba Bawaskar has been bringing thousands of people dying from snake bites and scorpion stings back to life. He is known for managing and pioneering research on scorpion stings and on snake bites in rural Maharashtra, which has resulted in the startling drop in death rates due to these menaces in the state. The Indian Practitioner got a chance to engage with the humble doctor- about his life, work, and views.

Insights from the interview:

Q First of all, hearty congratulations to you on being bestowed with the prestigious Padma Shri award this year. From humble beginnings in rural Konkan to the noblest of professions, can you tell us how you, as a young boy who helped his parents in the fields went on to become a doctor. What inspired you to opt for the medical profession?

I was born in the 1950’s, in a remote, underdeveloped village called Dehed in Jalna district, Maharashtra in a farmer’s family. Since an early age, I used to help my parents in the farm. I was really fond of learning. Once, my parents left me at the village school with a small piece of slate, and a warning that I was to not lose the slate piece come what may as I would not be given another piece. I took care of the piece, as if it was my baby. During nights, while sleeping I used to put the piece of slate next to my head so that nobody could reach it. To save kerosene which was used in lamps and was very expensive, I had mastered the art of learning subjects within a short time as I used to read them with full concentration.

I have always loved reading books and have subscribed to several journals since 1981. In the days of my medical education, I had a board in my room that said, “Nobody is my friend except my books” which l love too much.

But as a child, I used to fall sick quite often. As we were poor, my parents would take me to the government hospital where I was made to wait for hours in a queue. The arrogant behavior of the staff at hospitals and the sight of neglected patients crying had deeply disturbed me. I was always criticizing the medical staff and doctors. Then one day, I decided that I should study hard, pursue higher education and work at a hospital.

Q What were the hardships and challenges that you had to overcome in your journey?

I recall several such instances. When I was young, I had to move to Buldana with my family so that my elder brother could complete his matriculation. Elder sons were given more respect and facilities in rural India, in those days. My parents wanted me to take up farming; however, I wished to complete my education. So, I started walking around in the markets and shops in search of work so that I could fund my education, but my attempts were futile. Eventually, a temple owner who had a bookstall gave me work. I used to sell diaries and calendars at the bus stand on Saturdays and Sundays and continue my education on weekdays.

I have even had to wash buffalos. During my matriculation and pre-medical education from GS college, Khamgaon, I was living with a friend at his house. However, the owner of the room had taken objection to this and used to make me wash his buffalos in the mornings.

Later, after securing a good score, I joined the Government Medical College, Nagpur. However, coming from an impoverished, illiterate background, I found it difficult to cope with my peers due to cultural differences. I was often a subject of ridicule owing to my clothes and vernacular accent, because of which I suffered from depression. I took a year-long psychiatric treatment that involved ten sittings of electroconvulsive therapy, which helped me, get better and complete my medical degree.

Q Could you tell us how you came to be interested in the area of snake bites and scorpion stings?

A childhood friend of mine was once bitten by a cobra while working in the paddy fields. His condition was serious. I urged the villagers to take him to a hospital, but my advice was neglected. He died in the village temple without any medical intervention. This incident was extremely upsetting for me. Later, at the age of 16 while walking through the road, I suddenly experienced an excruciating pain in my right foot. I looked down to find a huge scorpion crawling. I have known the pain of scorpion stings and snake bites since childhood, which got me to be interested in the field.

Q What were some of the challenges you faced in your professional life?

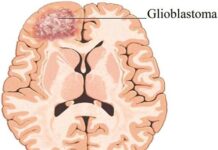

I was posted at a Primary Health Center in Birwadi, which falls under the Raigad district as part of my MBBS residency. Deaths due to scorpion stings was routine phenomenon at the PHC. On a daily basis, I would examine at least one case of pulmonary edema and subsequent death due to it. Previous PHC Records and discussion with peripheral doctors and professors of medical colleges were often unfruitful and non-contributory. Hence, I decided to study the clinical effects of envenomation in detail, which was later published in The Lancet.

Later, when I was posted at BJ Medical College, Pune, I was preparing a paper on scorpion sting data collected at the PHC in Birwadi. But news of my study on scorpion envenomation published in The Lancet spread like wildfire and subsequently, one of my professors persistently asked me to include his name in the paper on scorpion stings. When I fleetingly denied his request as he had not contributed to the study or examined any of the victims, he refused to register me for post-graduation. Back then, most of the data published by postgraduate teachers were of their students. However, times have changed and nowadays editors ask every author to give in writing about their individual contribution to the research. Eventually, I did receive my post-graduation registration after the professor’s departure from the college.

Q Could you share with us any interesting incidents/anecdotes in your life, in your educational field and your professional service that is worth recounting? Any interesting episode that had a life changing impact or even amusing instances?

One such incident that comes to mind was during my time at the PHC in Birwadi. Patients afflicted by snake bites, scorpion stings, pneumonia, dysentery, etc. as well as pregnant women were being brought to the health center in bamboo baskets, owing to poor transport facilities. This would cause delays and patients were often brought dead to the hospital. Scorpion sting cases with pulmonary edema did not respond to routine decongestive treatment and in most cases, resulted in death due to refractory pulmonary edema. I used to sit and record vital data of the patients. Once, a 32-year-old mother was admitted to the PHC along with her 6-month-old baby. She was stung by a scorpion. She was sweating profusely and vomiting continuously. She also had an elevated blood pressure and increased heart rate, all resulting in pulmonary edema. By morning, she was expectorating blood-stained sputum and had become dyspnoic and cyanosed. Cradling her baby to her bosom, she eventually succumbed to pulmonary edema. This incident had a huge impact on me, and I then took an oath to continue my work to find a solution to this life-threatening condition.

Sodium nitroprusside (SNP), a gold standard vasodilator, reduced both preload and left ventricular impendence (afterload) without raising heart rate. I hypothesized that scorpion sting victims may recover from pulmonary edema if SNP was used. After my MD Medicine, I requested a transfer to a rural hospital Poladpur close to the PHC Birwadi and took a few ampoules of SNP with me.

Once, a 7-year-old child stung by a scorpion was brought to the Rural Hospital in Poladpur. The child had developed pulmonary edema. After seeking permission and having an in-depth discussion with the child’s father warning him about possible side effects, we decided to administer SNP and ourselves, closely monitored the child’s pulse rate, blood pressure, respiratory rate and temperature as there were no high-end devices available to monitor the child’s condition. After around 6 hours or so, the child started to recover from pulmonary edema. I was so relieved that I started dancing about the place. However, my happiness was short-lived when I received a telegraph that evening about the demise of my father. I was in a dilemma if I should go back and attend the funeral of my father or if I should continue treating the child. After a lot of thought, I decided to stay back at the hospital and continued monitoring the child. Yes, as strange as it sounded, I decided to swear by the Hippocratic Oath I had taken during my graduation and skipped my father’s funeral to attend to the child. In the subsequent months, we treated more than 130 cases of scorpion stings with SNP, which was published in The Lancet in 1986.

PHC doctors were not allowed to use SNP for treatment. Hence, I was looking for treatments administered by doctors in peripheral regions to victims of scorpion stings, that is when I read about oral prazosin, which was called oral SNP.

Since the advent of prazosin, fatality rates dropped to almost <4% all over India, especially in coastal regions. Similar reports emerged from Israel, Saudi Arabia, Brazil and other countries where scorpions were predominantly found. We also found that anti-scorpion venom, prepared by Haffkine’s Institute scientists, combined with prazosin treatment led to rapid recovery, the results of which we later published in BMJ.

I used to arrange meetings with doctors from peripheral regions and PHC doctors every week so that I could train the latter on how to treat severe scorpion stings. Victims were thus, able to receive preliminary treatments at PHCs where they were brought after the sting.

Q India is home to nearly 300 different types of snakes. Despite a significant population of the country residing in rural areas where incidences of snake bites are widely prevalent, according to you, what kind of reforms in medical infrastructure would be needed to face this challenge successfully in India?

Enough quantity of ASV must be available at primary health centers and rural hospitals. Photographs of preserved specimens of venomous snake species should be circulated locally. Peripheral doctors and hospital staff should be given appropriate training to handle such cases. The people should be made aware of various signs and symptoms of snake bites as well as available treatments. No victim afflicted by a venomous bite with envenoming should be transferred from the primary centre that they have been admitted to unless full dose of ASV is administered. Centers must be prepared with necessary equipment for diagnosis as well as treatments.

Moreover, Doctors should be trained to perform resuscitation, including endotracheal intubation. They must be aware of how to use Amboo bags and ventilators and must be present throughout while transporting patients to higher centers.

Fair compensation to PHC and rural doctors as well as hospital staff is necessary. Services provided in the late hours by medical officers should also be fairly compensated.

Dr Bawaskar runs a small hospital with his wife, Pramodini Himmatrao Bawaskar, who also has an MBBS degree. “We have no staff in the hospital, just the two of us along with a helper,” says Dr Bawaskar. They together treat acute life-threatening emergencies at the hospital, provide emergency relief to victims and later transfer them to higher centers.