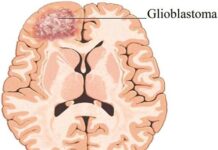

More and more mutations clutter up our DNA as we age. Mostly, these don’t cause problems. But sometimes, a switch will flip, and a mutated cell turns cancerous. Can we see this shift in time to prevent or treat cancer before it starts?

Led by researchers at Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, a scientific team that studies a precancerous condition of the esophagus (called Barrett’s esophagus or BE) are working to answer this question. In work published in Nature Communications, the team revealed that DNA changes in BE cells that presage esophageal cancer can be spotted years before cancer develops.

The characteristic changes include rearrangements of large chunks of DNA and damage to both copies of a tumor-suppressing gene called TP53.

Though the team’s ultimate goal is to improve diagnostics and screening for esophageal cancer, Dr. Thomas Paulson, a senior staff scientist in the Grady Lab who co-led the project emphasized that this study compares the mutations and DNA changes that occurred in patients who progressed to cancer with those that occurred in patients with stable, benign BE. While the findings are significant and are based on analysis of over 400 tissue samples, results from this 80-patient study would need to be validated in other patient groups before they could be used clinically to predict whether other BE patients will progress to cancer, he said.

“Once you progress to an advanced esophageal adenocarcinoma, treatment options are quite limited,” Paulson said in a news release. “If you can find the tumor when it’s very small, even microscopic, the treatment options are much better.”

The BE team undertook a sequencing study that covers all the DNA in a cell (known as the genome) in 427 tissue samples. “Most progressors had two hits in TP53,” said Paulson. Two hits would suggest a person is at very high risk for progressing from BE to cancer, though occasionally a person with one hit may also progress, he said. Patients who progressed to cancer also had TP53 mutations in larger regions of tissue, compared to the single-hit, localized lesions in non-progressing patients.

If both copies of TP53 in a person’s cells are broken, it’s very difficult for them to fix damaged DNA. This leads to duplications, deletions or reshuffling of large pieces of DNA. In fact, the team saw that BE cells in patients who progressed to esophageal cancer were much more likely to contain these large, complex changes than cells from those who never progressed.

The team hopes their findings provide insights to other cancer researchers. They think that the genetic changes they spotted may reveal insight into how cells evolve to cope with stressful conditions — and how those coping mechanisms can backfire — and go beyond esophageal-specific cancer mechanisms.